Tuesday night, Naomi and I sat down to dinner and tried to think about something other than the worst massacre of Asian Americans in recent memory.

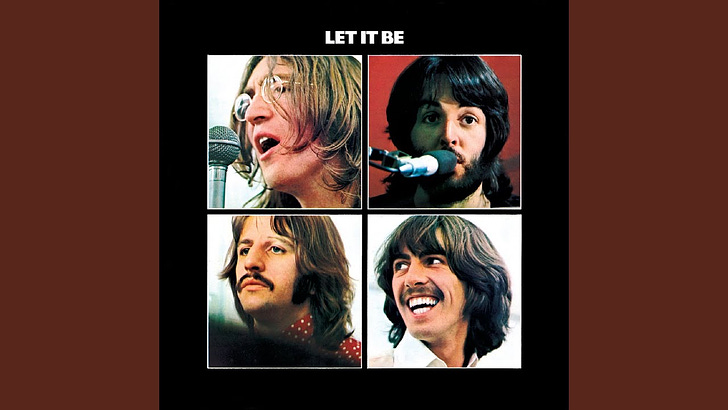

We usually either listen to a podcast or music over dinner. I wanted to listen to Let It Be. It’s a relatively rare pick—usually when it’s a Beatle evening, Naomi goes for Rubber Soul while I go for either the White Album or one of the Live at the BBC collections. For a long time in my life, Let It Be existed in a space between “good” or “bad” Beatles albums. It just was, like the Bible or Christmas or eight course Cantonese dinners with my extended family. An ontological category unto itself.

I’m pretty sure it was the earliest Beatles album I heard growing up. In her household, George’s solo work predominated. As the blood of massage parlor workers dried on the floor of 3 Atlanta spas 400 miles away—the fruit of a Southern Baptist’s supposed war on his self-described “sexual addiction,” which just so happened to focus exclusively on Asian women—we wondered how a song about Hare Krishna could become beloved by devout American evangelicals. George’s lush production and wistful timbre, shot through with a sense of the beyond intelligible in any grammar of divinity, probably didn’t hurt.

Naomi and I share a sense of the melancholy. Now that I think about it, I suppose that’s borne out of the way our childhoods were saturated in the grey morning light of the early Seventies. That period, between the end of the Sixties and the onset of heavy metal, seems to me wrapped in a very particular subtle sadness. A sadness in modest dress, not the outlandish folk outfits of prog rock or the Goth makeup of New Wave or, God forbid, the eyeliner and Spandex of Eighties hair metal.

Marathon sadness, not crying jag, 100-meter-dash sadness.

Listening to the album, we debated how much John’s voice sounds like George’s on “Across the Universe.” (No doubt his most George-like song, not least because of its very un-John-like foray into mysticism totally unburdened by irony.) I felt compelled to point out that when John sings “I pick a moondog” on “Dig a Pony,” he’s referring to one of the early names of the band. Naomi remarked that humanity would probably be better if everyone listened through the Beatles’ catalogue. I had to agree.

I wonder if any of the murdered victims had a favorite Beatles song.

Then we got to the actual song “Let It Be.” On the record, John, clearly embarrassed by what he thought of as a song drenched in unbearable sentimentality, has to open it with a joke: speaking in a cut-rate-Tiny-Tim sort of voice, John squeaks, “And now we’d like to do, ‘Hark the Angels Come.’” Then the song starts: those simple piano chords cycling through one of the most pervasive progressions in popular music; Paul launching into lyrics that are sort of about heartbreak generally but also absolutely about the Beatles’ breakup specifically; Ringo hitting hi-hats to which Phil Spector later added gobs of tape delay; John creeping in on bass as the absolute bare minimum form of collaboration with his eternal frenemy Paul, who wrote the song.

I used to think this song was by John, actually. Somewhere, buried in reams of notebooks from my childhood, there’s a laborious poem about the Beatles that I probably wrote after struggling my way through one of the many biographies I devoured at that age. I’m pretty sure there’s one line about “Let It Be” being John’s song. I didn’t understand that the song was too straightforward for John, too quietist, too churchy.

But like it or not, churchy quietism is a dimension of human experience that will always be with us and that we frankly often need, temporarily and under specific conditions, such when one is trying to process the fact that a guy with a gun drove up to three different “Asian” massage parlors to murder human beings, before being apprehended without any of the brutal force applied to George Floyd or Rayshard Brooks or Breonna Taylor or any of the other names we can never forget.

Yeah, at least temporarily, at least to catch one’s breath in the thousand-mile endurance challenge that is life on planet Earth, one has to let it be.

Beatleheads know that there are a few versions of “Let It Be” floating around. There’s the original Phil Spector-produced version, and then there’s the “Naked” version, which has a different solo, different vocal takes, and none of Spector’s orchestral flourishes. Purists, I’m sure, prefer the latter, mainly because the band’s distaste for Spector’s production is a matter of legend. But for me, the album version will forever remain superior. It’s the one that looped on long car rides when for whatever reason our family would be piled into my dad’s beige Mazda MPV, listening to the multi-CD player that occasionally (frequently) skipped. It’s the one I learned to play for my Chinese immigrant church’s New Year’s Eve talent show when I was 12 or 13.

Most importantly for me, it’s the one that has That Guitar Solo.

George’s solo on “Let It Be” was like the Alpha and Omega of my guitar instruction when I was first starting out. The way I said Kurt Cobain thought about anger last week, George’s solo illustrates the way he thought about loss. It’s not about fretwork or fancy technical wizardry. It’s about trying to shape bereavement into some kind of temporary order, even (don’t say it too loudly) some kind of hope.

That night, the same night bullets drowned out the sound of music, we listened to the Beatles’ “Let It Be” back-to-back with Aretha’s incredible cover. Aretha’s voice on that cover is like George’s guitarwork translated into the grammar of Black gospel and metamorphosed into a human voice. Listening to them one after the other, George’s gently weeping guitar giving way to Aretha’s defiant altar call, I thought about call and response. I thought about the Black church inspiring Fifties rock and roll inspiring Sixties rock inspiring late Sixties r ‘n’ b. I thought about how “Let It Be”’s white gospel, ultimately devoted to nothing more seismic than the breakup of a pop group, transfigures into a revelation for Civil Rights icons like Aretha: after Malcolm’s and Martin’s assassinations, after Fred Hampton’s murder, after all the marching and all the singing and all the newshour drama gives way to a crepuscular exhaustion.

Aretha overcomes John Gabree’s sniff that the song’s lyrics are “dangerous politically.” The way she leans into the line “There will be an ans-werrrr,” like a call to arms in the middle of a song about laying them down, reminds us that there’s no chance in hell that the struggle is actually over. In her hands, “Let It Be” isn’t about resignation. It’s about recuperation in the midst of a long marathon.

The Eschaton is a long marathon. All the interlocking pathologies that have produced America’s (and the global world-system’s) protracted disintegration; all the BREAKING headlines that cumulatively sabotage one’s emotional compass; all the repetitions and looping restagings of avoidable disaster and sanctified violence and institutional corruptions; all . . . that . . . shit . . . just . . . keeps . . . running . . . on . . . and . . . on.

I wish I could end this post by saying that listening to the Beatles and Aretha was a road-to-Damascus moment, Wordsworth’s spot of time in which the child-as-the-father-of-the-man makes his presence felt in a song from preadolescence, bla bla bla. It was a quieting moment that centered us in the middle of a whirlwind. But it wasn’t the road to Damascus. Genuine and unconstrained epiphany, even when it briefly teases us with its presence in the musical triumphs of the dead, seems impossible to really lay hold of. It feels like you can only get at it after the fact, writing retrospectively about what you might have really felt in the seconds when God might have been speaking to you out of the whirlwind, through your laptop’s shitty sound system, the same laptop through which you glimpse over and over the pixelated dying of some collective light.

Meanwhile, the whirlwind keeps on blowing. It won’t let us be, not for a second.

GoFundMes for the Atlanta spa shooting victims’ families

Red Canary Song, a Chinese massage parlor coalition

Sign the open letter on anti-Asian racism and Christian nationalism